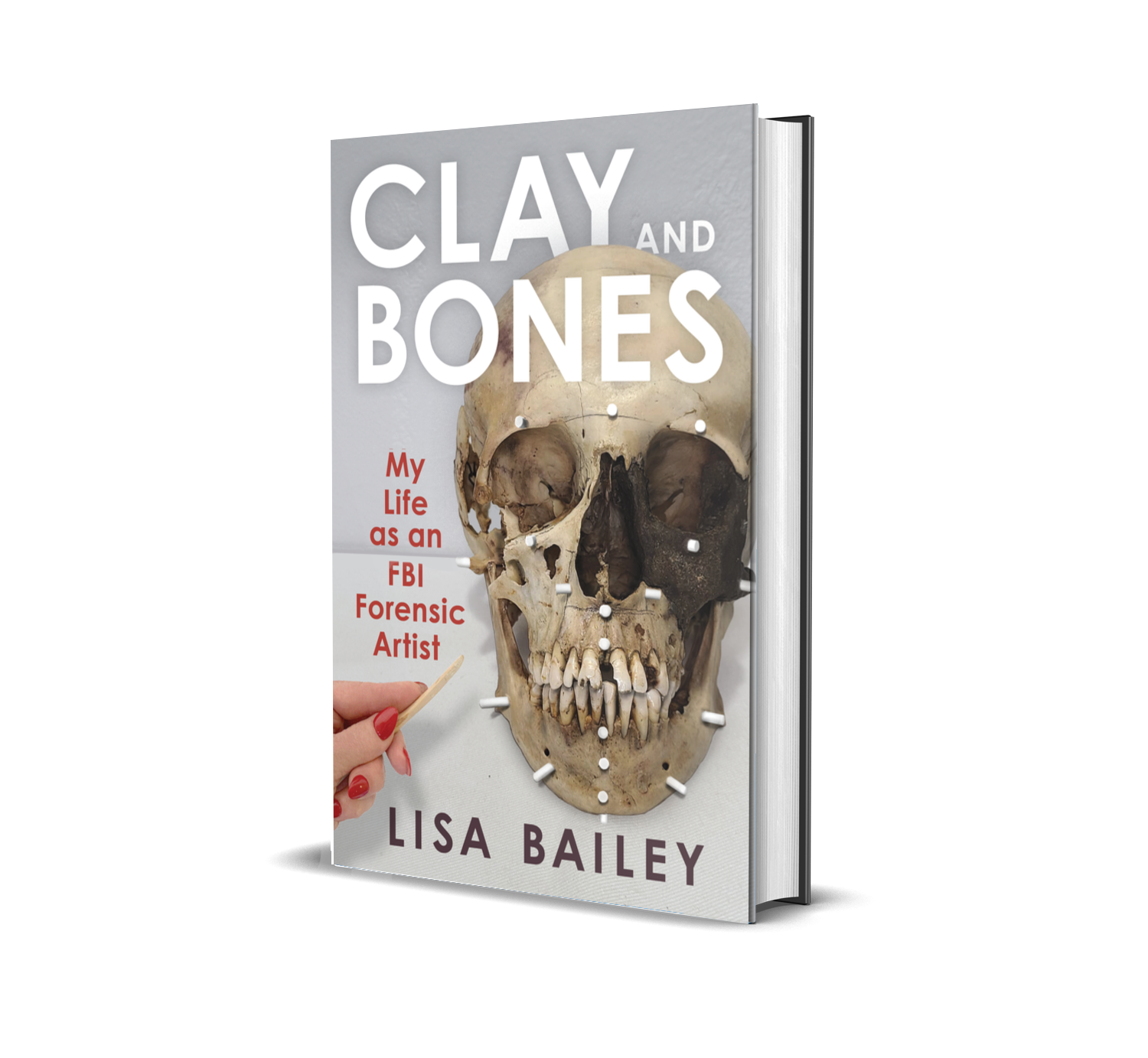

“Clay and Bones” follows Lisa Bailey’s extraordinary career as

an FBI forensic artist, from the aftermath of 9/11 to sculpting the faces of the unidentified dead,

while battling the Bureau’s entrenched culture of sexism and retaliation.

Clay and Bones

My Life as an FBI Forensic Artist

Just two months after the September 11 terrorist attacks, Lisa Bailey began her career as an FBI forensic artist.

She threw herself into the work, and over the next eighteen years handled hundreds of cases: unidentified remains pulled from shallow graves, sexual assaults, acts of terrorism, and kidnappings. She became a recognized authority in facial approximation from the skull, witnessing firsthand how her sculptures could restore a victim’s identity and bring closure to grieving families.

But even in those early days, Bailey noticed cracks in the Bureau’s polished image. She’d heard stories of women who reported harassment or discrimination, only to find themselves quietly dismissed. She wanted to believe the rumors weren’t true…then it happened to her. Now, Bailey breaks her silence in this raw, eye-opening account.

She takes readers behind the scenes of the Bureau’s most haunting cases, from mass disasters to cold-case homicides, and exposes the hidden toll of a career inside one of the world’s most powerful law enforcement agencies.

She describes the painstaking art of restoring a face from an unknown victim’s skull, the profound relief of a confirmed identification, and the eerie reality of working among the dead at the University of Tennessee’s famed “Body Farm.”

Told with candor, grit, and dark humor, Clay and Bones offers a rare glimpse into the macabre yet meaningful world of forensic art, and the resilience of a woman who refused to be silenced by the very institution she served.

What People Are Saying

“From investigations of charred corpses to intensive work on boxes of unidentified skulls, Clay and Bones is a gripping account of the day-to-day duties of an FBI forensic artist. And if you think reconstructing someone’s face from decades-old remains is Bailey’s most difficult challenge, you’re in for a big surprise."

— Lindsey Fitzharris,

New York Times bestselling author

“Clay and Bones shines a light on a crucial position in law enforcement while also revealing systemic flaws at the premier U.S. law enforcement agency. Readers will be mesmerized by her work and angered by the targeted harassment she received."”

— Booklist

“A fascinating account! Lisa Bailey deserves both our deepest respect and our profound admiration. I say this in tribute to her incisive intellect that led to groundbreaking work in forensic investigation (and) in honor of her unflinching courage in face of the flagrant gender discrimination and despicable administrative dishonesty she was forced to endure in her FBI workplace. ”

— Douglas Schofield, coauthor of Giovanni’s Ring: My Life Inside the Real Sopranos

Lisa Bailey is a former FBI forensic artist who specialized in forensic facial approximation—the process of estimating an unidentified person’s face based on the shape and features of their skull. As the first female forensic sculptor in the FBI, her work has aided in the resolution of numerous cold cases involving unidentified remains. Over her 18-year career, she worked on hundreds of cases, including child abductions, homicides, sexual assaults, acts of terrorism, and fugitive investigations.

Excerpt

Chapter 1: You Had me at Decomp

The stench of rotting flesh hit us as soon as we stepped out of the car, and once it grabbed hold there was no escape. Hours later I could still feel it on me, and it was several days before I stopped imagining catching whiffs of it.

Amy, our guide for the day, offered us face masks, but we all declined. If she wasn’t wearing one, then we weren’t either. If we had any sense, we would have accepted, but none of us wanted to look as if we couldn’t handle what was coming. After all, we were from the FBI; we could tough it out.

Bug spray was another matter entirely. I wasn’t about to turn that down. This wasn’t just about preventing mosquito bites or Lyme disease. I knew any insects within a one-mile radius would have just finished nibbling on rotting corpses, and I wanted to keep them as far away from me as possible. A cartoon vision of a bug wiping its dirty feet on me like a welcome mat popped in my head, and I laughed to myself. It wouldn’t be so funny if blow flies or maggots ended up in my hair, so I grabbed the insecticide again and kept spraying until the can hissed that it was empty.

Lavender gloves and baby blue booties were handed out next, the same kind doctors and nurses wear. For the next hour we’d be walking through mud, muck, and a host of bodily fluids.

I stared at the chain-link fence topped with coils of barbed wire. This wasn’t the strongest of security measures, but then again not too many people tried to get inside anymore. Apparently, the shock value of having hundreds of naked bodies lying out in the sun had worn off. When the Body Farm first opened in 1981 there was plenty of outrage, not to mention a few drunken teenagers scaling the fence to see inside the only facility dedicated to the study of human decomposition. Now, the residents of Knoxville, Tennessee, didn’t just accept this patch of land and what it stood for, they were downright proud of it.

Amy removed the heavy metal lock from the hinge, and the gate creaked open. “After you,” she said. And there it was. The wholly generic, yet infamous battered metal sign propped against the fence in the dirt: “Anthropology Research Facility – For Information Call Dr. William Bass.”

It took a moment to sink in. Not many people get to stand where we were right now, and we weren’t about to take it for granted. Wade and I just looked at each other and laughed. He was a forensic artist like me, and the only other person in our group who appreciated skulls as much as I did.

Our photographer, Geoff, had wandered off in search of photos, while Kirk, the 3D modeling expert, assessed the surroundings. He built crime scene models for court, and his brain always worked overtime looking for a bigger, better, or faster way to build something.

Amy made her way toward a cargo van parked beside a shed. She eyed Wade and Kirk. “You guys feel like doing some heavy lifting?” They looked at each other and shrugged in agreement. When else would they get a chance to move a dead body?

“We only used to get a couple each year,” Amy explained, “but now we get over a hundred. That’s why this one is going straight into the freezer, at least for now.”

“Freezer? Where?” I asked. All I saw were trees. Amy nodded toward a tool shed that I had mistakenly assumed contained tools. “Over there.”

She held the door open while Wade and Kirk slid the body out of van and adjusted their grip. It was wrapped in a heavy layer of white sheets, and was still frozen solid, having made the 3-hour trip packed in dry ice. Taking up most of the space inside the shed was a plain white freezer, the big top-loading kind that your grandmother used to have in the basement, the kind you were sure held dead bodies and monsters instead of hamburger and leftover lasagna. Here is where you realize your childhood nightmares weren’t so off-base after all; not only were there bodies in this freezer, but they had actually volunteered for the job.

The cadaver that Wade and Kirk were maneuvering into place was part of the Anthropology Research Facility’s donated collection. When it first opened, the collection contained anonymous, unclaimed corpses acquired through the state medical examiner’s office. As time went on, body donation became a viable alternative for families who were either unable to pay for a burial, or chose it as a way to support research in forensic science. The facility will pick up a body within a 100-mile radius and transport it for free.

Now there was actually a waiting list, with over 4,000 willing participants pre-registered for a spot on the grounds. Once the bodies are “done,” their skeletons are thoroughly cleaned, packed in long cardboard boxes, and stacked on sturdy metal shelving at the university. “Any other bodies you want us to move, lady?” Kirk joked.

Amy smiled. “I think one is enough for today. So, where do you want to start?” We all looked around at once. I pointed to a pair of feet with cherry-red toenail polish peeping out from under a black plastic tarp, the loose corner flapping in the breeze. “That one?” I asked.

“Sure,” Amy replied. “We only put her out yesterday, but let’s see what’s going on under there.” She knelt down and peeled back the heavy plastic. “Oh wow! See here? Something’s been chewing on her legs. That didn’t take long!”

We learned in for a closer look. “So, what would have done that? Rats?” I ventured.

“Sure, could be rats. Or maybe squirrels.”

“Really? I thought squirrels didn’t eat meat. Or at least, they didn’t eat people.”

“That’s what I thought, too. But we’ve got video.” Amy stood up and pointed to several cameras mounted to wooden posts. “Don’t trust raccoons, either. They aren’t as cute as you think they are.” Amy brushed off her slacks and motioned for us to follow. “I’ve got another that’s been out here for a few weeks. But he’s deeper in the woods, in the shade.”

Well, this isn’t so bad, I thought. I can’t exactly say that I was getting used to the smell of things, but the visuals were so surreal, and so fascinating, I didn’t have time to think of being nauseous.

My bravado wavered at our next stop. I couldn’t tell whether the body was young or old, male or female, but one thing was for certain: it was huge.

“This one’s pretty bloated, so be careful. He could go any minute.” Amy said. Please don’t explode, please don’t explode, I sang to myself, as I nodded and crouched down. I’d heard that bodies in the late stages of decomposition could “pop,” and in my mind Amy had just confirmed it. As it turns out, bodies don’t actually explode in one spectacular burst; the skin ruptures and tears apart slowly, leaving ample time for a running head start in the opposite direction.

I inched closer to take pictures, trying my best not to breathe in too deeply. As bad as the smell was from the parking lot, it was a thousand times worse close up. It was then I saw the mass of maggots crawling around the face. Suddenly the jokes we’d made about having tapioca for lunch didn’t seem quite so funny.

By now I was regretting not wearing a mask, but it wasn’t because of the smell. This was the middle of July in Tennessee, and thousands of gnats swarmed in heavy clouds as we walked among the trees.

The thought of inhaling those tiny, venomous insects would be enough to send me over the edge. I pretended to turn my head to sneeze, tucking my nose inside the elbow of my shirt to breathe. I looked up at the bright blue sky and focused on seeing shapes in the clouds. Anything I could think of anything to take my mind away from the sights, smells, and sounds of human decay.

Why did maggots have to sound just like someone chewing a sandwich with their mouth open? Would this smell ever come out of my clothes? And why did it have to be so darn hot? I was desperate for a cool breeze. Whose bright idea was this, anyway? Oh, yeah; it was mine.

It’s not as though I woke up one day and thought, I want to gross myself out in the most expedient way possible. But the project we were working on was the first of its kind, and a veritable gold mine of information for forensic artists. What we were doing could help identify thousands of bodies buried in unmarked graves and help bring closure to families searching for missing loved ones.

If you’ve ever seen CSI, then you know that the process of doing a forensic facial approximation is pretty straightforward. An artist glues thin rubber erasers to a skull and fills out the spaces in between with clay to create a face. The sculpture turns out to be a perfect likeness and the victim is readily identified.

If only it were that easy. While the skull does hold clues as to what a person will look like, there are still many unknowns. And that’s the part that drove me crazy. Whenever I see an interesting-looking person, I try not to stare while I think: What is going on under there? Why does she have a dimple on one cheek but not the other? What causes her eyelids to fold that way? Why is her right eye higher than the left, and was she born with that nose or did plastic surgery have something to do with it?

In a perfect world, I would be able to find answers in a photographic collection of both skulls and their corresponding faces, but there was no practical way of putting one together. Forensic artists check the accuracy of our work based on the identifications we get, but we aren’t able to share that information with each other. The moment a skull goes from being a number to a name, it has an identity and rights, as does the decedent’s family members. Artists needed real-world examples for comparison and education, but we couldn’t get them without permission of the victims’ relatives. And that’s just something you can’t ask of a grieving family.

It was after reading Dr. Bass’s book, Death’s Acre, that the answer came to me. I was thinking of donating my body to science, and what could be a better choice than the Body Farm? As I filled out the research facility’s online donation form, I noticed a check box for submitting a driver’s license photo. I blinked my eyes to make sure I wasn’t seeing things. Photos! The Body Farm had photos of known donors! Plus, they had donated themselves, so permission had already been granted to use them for research.

I was so excited I could barely see straight, and my mind went into overdrive: I’m going get a team together and go there. We’ll scan every single skull and get every photo they have. We’re finally going to figure some things out, and when we do, every forensic artist will know about it, too!

I envisioned advanced facial approximation classes at the FBI’s training academy, with reference catalogs that could be shared among artists. Maybe even a secure, online database with 3D models of the skulls. The possibilities seemed endless, and as the Body Farm collection grew, so did my enthusiasm.

I’ve seen some ghastly things over the years, like what happens to you in a plane crash, or seeing definitive proof that having “your brains blown out” is not a euphemism. This sort of thing hadn’t been covered in the job interview, and it’s probably for the best, because I might have backed out had I known. But now I could look at dismembered heads while eating a cranberry muffin and not think a thing about it.

“How did you ever get a job like this?” It’s always the first question people ask me and I don’t mean to be vague when I say, it just sort of happened.

For me, it took an enlistment in the navy, and years of working in jobs I hated while earning my degree in art. Then, somehow luck, timing, and preparation converged, and I ended up landing the best, and dare I say coolest, job on the planet. The job didn’t come to me easily by any means, and for a long, hideous period in my career I had to fight tooth and nail to keep it.